Kumar's big bets

- Copy

T. Surendar

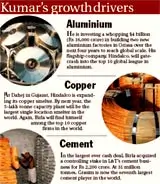

Kumar's growth drivers | aluminium| buildingthe competencies | copper| managingthe transformation: what Kumar inherited| cement

"By and large, the restructuring phase is behind us. Now the focus is on growth. And growth is always more exciting"

These days, the managers at Hindalco aluminium factory in Renukoot, near Varanasi, have only one question on their minds: when will their group chairman Kumar Mangalam Birla pay them a visit? Kumar Birla hasn't been to Renukoot for nearly four years. But he would know what the 12,000-odd managers and workers there have collectively achieved — not only does it bring in a fifth of the group's sales, it now also ranks among the best run aluminium factories in the world. The factory, which began commercial production in 1962, continues to be a jewel in the crown of India's third largest conglomerate. Incidentally, it is also the same place where Kumar's father, the late Aditya Birla, first sent the young Birla to train after he returned to the country from the London Business School. Last weekend, Birla was in Varanasi to receive an honorary doctorate from the Benares Hindu University. Yet, he still couldn't pay a visit to the factory.

Now, this would seem rather unusual for Birla, who seldom misses an opportunity to meet his employees. But then, these are unusual times for the Aditya Birla Group. For the past few weeks, Birla has been ensconced in high-level business strategy reviews with his top managers. Insiders say the meetings, at his fifth floor office in the spanking new corporate office in Worli, Mumbai, often last more than three hours at a stretch — and sometimes drag well into the night.

There is a good reason for these confabulations: the group is in the process of completing a massive investment plan in line with Birla's new growth strategy — and on a scale which is unprecedented in the group's 57-year old history. Over the next four years, Birla plans to invest a whopping Rs 20,000 crore across his businesses — primarily in aluminium, copper, cement and fertiliser. For a comparison, in aluminium alone, the group will invest more than it has done in the last two decades. Birla had spent a better part of his time trying to untangle his existing jumble of businesses and driving operational efficiency. Today, the group is sitting on piles of cash. Birla's three flagship companies — Hindalco, Grasim and Indian Rayon — collectively threw up close to Rs 3,000 crore of free cash flows in 2003-04 alone.

Clearly, Birla has now chosen to shift gears. The next few years marks an inflexion point within the group. For the first time, Birla is beginning to think big, really big. In the past, Birla was simply focused on extracting value rather than betting big on growth. He typically chose to add capacity in small chunks or acquire healthy, but relatively small, businesses. Consider a couple of his big bets: in 2000, he bought the Rs 1,750-crore Indal, which added a third to his existing aluminium capacity. After that, it took him an agonising 36 months to clinch a deal with Larsen & Toubro earlier this year to buy a Rs 2,500-crore cement business that was almost as big as his own.

Most of these deals are small compared to what Birla now has up his sleeve.

Insiders say that Birla is close to finalising a mammoth Rs 16,000 crore investment plan over the next four years for his aluminium business. The plan, drawn up by Hindalco managing director Debu Bhattacharya, includes setting up two new plants. So far, the board has not yet seen the plan. But when they do and ratify it, it will increase Birla's aluminium capacity three times over, all at one shot, and pitchfork him into the global top 10 producers' list. Besides, for the first time, Birla will be even taking a few risks by his standards. Not only will the Hindalco expansion suck out much of the cash in the group, it will force Birla to take on some more debt — something he has shied away from doing for a long time.

If things go according to plan, the rewards will be big too. When the two new plants become operational in a little over four years, the Rs 6,800-crore Hindalco will be almost as big as the group is today. And in nearly half the time that Birla took to increase the entire group's sales from Rs 7,200 crore to Rs 28,000 crore after he took over the helm. Says Bhattacharya: "Our plan for aluminium is unlike anything we have done before. It will take us into a different league."

It is about time the group began cranking up its growth agenda, some would argue. A decade ago, the Aditya Birla group was the second largest conglomerate in India with a sales of Rs 6,500 crore, ahead of the Ambani-led Reliance Industries, and behind the Ratan Tata-led Tata group (Rs 15,000 crore). Since then, the Reliance group has zoomed past both the Tatas and the Birlas to the No. 1 slot. Its turnover has shot up to Rs 99,000 crore on the back of aggressive expansions in petrochemicals and refining. And the Tata group's turnover has grown to Rs 65,000 crore, led by the two flagship companies, Tata Motors and Tata Steel. The Aditya Birla group's turnover now is just Rs 28,000 crore. Now, though Birla has managed to show better profit margins in most of his businesses, his companies have grown slower than that of his peers. The stock markets seem to have noticed too. The Birla group's current market capitalisation, at Rs 30,000 crore, is just over a third of Reliance's or Tata's. Even a first generation entrepreneur like Sunil Mittal today commands a market capitalisation of Rs 25,000 crore for his flagship company, Bharti Televentures. Says a leading mutual fund manager: "Conglomerates are all about size and scale. Birla was talking of value creation when his peers were thinking big. The market was not convinced."

The new growth gameplan should address some of that concern. Much of it is in line with Birla's portfolio strategy — something that he devised with the help of the Boston Consulting Group. Consider how. In the last eight years, Birla has consciously shifted the focus of his overall portfolio from predominantly fibre-based businesses to one that is now driven by non-ferrous metals. The share of textiles has since dropped from a quarter of the group's turnover to below 5 per cent now. On the other hand, the share of metals and cement has increased to 62 per cent. Birla has also reduced the number of businesses and made small investments in new age businesses like software (PSI Data), business process outsourcing (Transworks) and branded garments (Madura Garments). And he has chosen to consolidate each of his businesses.

Having cleaned up the portfolio, Birla has now narrowed down his big bets to just two sectors: metals (copper and aluminium) and cement. The intent: to become globally competitive in all the three. The route: gain cost leadership. But just how will Birla get there? As things stand, much of his big investments in both copper and cement are over - and Birla believes he has secured his position in both businesses. So, he is now putting all his eggs in one basket: aluminium.

Aluminium

So why is Birla so excited about the opportunity in aluminium? And will it give him a tenable place in the global metals business? The confluence of four key issues has prompted Birla to pin his hopes on aluminium. One, in the last few years, the leading aluminium companies in the world - like Alcan (capacity: 3.5 million tonnes) and Alcoa (capacity: 4.1 million tonnes) - have begun a furious consolidation spree. They have bought out smaller players across Europe and the US. The 10 top players control more than 50 per cent of the market. In the process, greater scale has helped bring down the cost of production. Now, the price movements in the aluminium business are dictated by the London Metals Exchange (LME), which acts as the benchmark. So far, Hindalco is able to keep its costs down, and make hefty profits. Last year it released nearly Rs 1,500 crore of free cash flow.

Building the competencies

Kumar Mangalam Birla outlines four important factors that will determine his success in his new growth phase — scale, efficiency, management of cash flows and the skills development of his people. He acknowledges that it will be his people who will ensure that the other factors fall in place.

Till just a few years ago, nobody 'retired' in Aditya Birla group. When Birla joined the company, he worked with managers who were nearly thrice his age. Seniority determined hierarchy, rather than merit. Birla spent quite a lot of time to change this. He put up performance management systems, reviewed compensations and emphasised on training to bring in meritocracy.

Now, his emphasis on growth requires the next push on the people front. The group's HR head, Santrupt Misra, has been working on this for the last two years. Misra feels that for a company to achieve growth, the HR processes need to be accelerated. The key, therefore, lies in spotting talent and growing them for bigger roles quickly. In 2002, Misra c;reated a talent management pool that identified over 200 managers as performers and put them on a fast track to growth.

Misra feels setting bigger challenges and giving incentives to achieve them will be the key in preparing the organisation for growth. Says Kumar Mangalam: "The task is in differentiating between a good performer and a performer."

For any commodity, and aluminum is no exception, long-term viability hinges on the ability to produce it cheaply through the ups and downs of the commodity cycle. Currently, Hindalco's cost of production is among the top quartile of the world's best producers. But with a capacity of just 400,000 tonnes, it has remained a bit player. Even the 10th largest aluminium company produces 50 per cent more than Hindalco. As other companies start expanding, Hindalco's lack of scale will soon become a major handicap because it would have a direct bearing on its ability to keep costs low. Says Bhattacharya: "Staying in the business with the same capacity is like running on the treadmill. You just stay where you are." Fortunately for Hindalco, despite its late-mover status, it still has a window of opportunity to scale up and enter the global league. The 30-million tonne aluminium market is growing at 4.5 per cent every year. What is more, Asia is where the action is and the demand is red hot. China, Middle-East and South East Asia are soaking up capacity, creating a shortage of 2 million tonnes. And apart from a handful of smelters in India and China, there are no new capacities being built. Guangdong Fenglu Aluminium Company and Aluminium Corporation of China are just as big as Hindalco in size. These smelters cater to the fast growing domestic demand and, on the face of it, appear to be efficient, especially since prevailing commodity prices are high.

But once demand tapers off - and that won't happen in a hurry since the upturn in the aluminium cycle is just starting - it will boil down to the issue of global competitiveness. That is where Hindalco will enjoy a clear advantage. India has huge reserves of good quality bauxite ore, the fifth largest deposit in the world. Having smelters near the mine pithead will save substantial costs for an Indian producer, which will have a direct impact on profitability, especially in a downturn. A Chinese producer, on the other hand, has to import the ore and thus bear an additional transportation cost, denting their competitiveness.

Hindalco may be able to ward off the Chinese. But in the long run it will have to contend with formidable competition in its own backyard: from Sterlite. Its owner, Anil Agarwal, is a first generation entrepreneur who earned his spurs in the telecom cables business before diversifying into non-ferrous metals. Agarwal started off investing in copper, almost at the same time as Birla built his copper smelter in Dahej. In 1997, Sterlite bought over the Chennai-based Madras Aluminium, which gave him a small foothold in the aluminium business. Then, Agarwal's ambitions soared, as he attempted a hostile bid for Indal, which parent Alcan fended off successfully. In 2002, Agarwal snatched away the Rs 900-crore state-owned Balco — bidding far higher than Hindalco.

Realising the need to scale up, Agarwal is now going hell-for-leather to expand capacity. At Korba district in Orissa, Sterlite is putting up a brand new smelter using Chinese technology, which is 30 per cent cheaper than the commonly used Pechiney's technology. Sterlite will source bauxite from its Langigarh mines in Orissa, though it has still not got possession of the mines from the state government. But once the expansion does go on stream by March next year, Sterlite's aluminium capacity could well match Hindalco's — and at a competitive price. That's when Hindalco's numero uno position in the industry will be threatened.

Besides, Hindalco's own competitiveness is being eroded due to a set of factors. When Hindalco first set up the Renukoot plant, power was easily available from the nearby Rian dam. Bauxite also came from the nearby mines. As Hindalco expanded, it put up captive power plants to keep the costs low. But ore in nearby mines were exhausted. Now, the compnay has to transport ore from newer mines, in some cases, 200 kilometres away. It even buys some high quality ore from Gujarat.

As a result, Hindalco's cost of sourcing bauxite is now higher than the state-owned Nalco, which has a factory located at the bauxite mine pithead in Orissa. However, Hindalco's costs are still lower due to the lower power cost. Still its competitive edge will get dented as the mines go further away.

So how do Debu Bhattacharya and his team maintain the competitiveness of the business? One option is to locate a new plant at the pithead, where power is also easily available. The new capacity — an additional 3.5 lakh tonne — would then help offset the higher costs at Renukoot. Says Bhattacharya: "We can reduce costs only to an extent. Beyond that, there is a crying need to increase scale."

The Rs 16,000 crore investment plan for aluminium will flow into two projects — the Utkal Alumina Project and the Aditya Aluminium Project — both based in Orissa. The eastern state has by far the biggest reserve of quality bauxite comparable to the best in the world. (Which explains why global mining giants like the $15-billion BHP Billiton have chosen Orissa as a destination.)

The two projects are somewhat different from each other. Aluminium is made by a two-stage process from bauxite. Bauxite is found mixed with red mud, 3-4 metres below the surface. First, an intermediate, alumina is extracted from this bauxite ore. Three tonnes of bauxite is needed to extract one tonne of alumina. Thereafter, the alumina is reduced into aluminium metal by an electrolytic process in a smelter. The second stage requires a lot of power — which can account for up to 40 per cent of the total costs. So, companies could choose to make alumina or aluminium depending on the cost of power. For example, the United Arab Emirates has emerged as a good location to put up a smelter since power costs are far cheaper. As things stand, there e;xists a robust market for both aluminium and alumina.

In the Utkal project, where the Birlas have a 55 per cent stake along with Alcan, the plan is to have a 1.5-million tonne alumina plant. This project has been on the anvil for six years, but never took off because the government could not rehabilitate the people living on the mines. Now, the problems seem to have been sorted out and the Birlas should be awarded the mining lease shortly.

With the Aditya Aluminium project, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Hindalco, the group will now have a 1-million tonne alumina capacity and a smelter for 350,000 tonnes (the biggest size available today). That will catapult Hindalco into the Top 10 aluminium metal makers in the world.

Today, the effective import duty for aluminium is pegged at 10 per cent. But to ensure that Hindalco's new projects remain competitive even if duties fall further, Bhattacharya says the plans have had to clear stiff internal hurdles for a host of financial parametres like the return on capital employed, the return on equity and interest cover on debt. And that too, assuming zero import duty on the metal.

Copper

Even as Birla cranks up his aluminium business, considerable focus is also on Hindalco's other big bet: copper. But unlike aluminium, where scale is the key driver, the story is different in copper. Here, Bhattacharya's expansion has more to do with being cost competitive rather than growing the business in size. There is a reason for that. When the Birlas first ventured into copper in the mid-1990s, they started the business more as a domestic play. The differential between the import duty for the metal and its raw material was high (nearly 30 per cent). This allowed local companies to earn a good margin in just being converters. There was also a robust demand for copper in jelly-filled telecom cables.

So in 1997, the Birlas, through their fertiliser company Indo-Gulf, put up a copper smelter along the port in Dahej in Gujarat. So that they could import the metal easily. Of course, they had to contend with the same infrastructural headaches that Indian industry continues to complain about. There was no infrastructure then available in Dahej to import large quantities of solid cargo. Birla then spent a considerable time, and money, setting up a port. No power was available on site, so he had to lay railway lines to transport coal for a new power plant. There were no housing facilities. So Birla had to build a township for its employees. None of this quite mattered then, since profitability was assured due to the import duty cushion and the reasonably strong international copper prices.

But by around 2000, import duties started coming down (now the duty differential has fallen to 10 per cent). That exposed chinks in Hindalco's strategy. There are typically two kinds of copper smelters: ones attached to captive mines and standalone ones, which buy ore from the market. When copper prices spiral upwards, the standalone smelters, like Hindalco's, end up paying a substantial premium for the ore. This disturbs their cost equations and leaves them scrapping the bottom for margins. There are two obvious routes out of this situation. First, Birla has to find a way to shore up his supply of ore. Second, he has to mitigate the additional investments made on infrastructure.

Luckily for him, the port in Dahej is the only bulk solid-handling port in the region. So Hindalco is allowing commercial access for handling vessels for third parties. Bhattacharya claims that has made the port self-sustaining. Next, to bring some cash to the business, the company began to convert sulphuric acid, a by-product of copper production, into phosphatic fertiliser and sell it. It also started recovering gold and silver from the smelter — all to extract a bit more value. Yet all this is still not enough.

A few months ago, copper conversion charges fell to almost a pence a pound. That really shook Birla. Bhattacharya says if the copper business is to be profitable in the long run, its efficiency would have to be in the top quartile among the world's leading manufacturers. Just like in aluminium. That means he has to increase capacity and use the additional volumes to spread his fixed costs further. That is exactly what he is doing, at a cost of around Rs 1,800 crore. Next September, when the copper expansion goes on stream, Hindalco will have the largest single location smelter in the world. The group is also buying a few more mines so that it can get 40 per cent of the raw materials in-house. That is when the conversion costs will be just 5-6 pence per pound, and Hindalco will find a place in the top quartile. Says Bhattacharya: "We have some way to go in copper. But we will surely get there."

While Birla lays a solid foundation for his metals business, he is also building up an impregnable position in cement. In July this year, the takeover of L&;T's cement business made Birla a clear market leader, at nearly 31-million tonnes, much ahead of the Gujarat Ambuja-ACC combine (28 million tonnes). Shortly after he took over L&;T's cement division (re-named as Ultra Tech), Birla sent a letter to all the employees. The group had paid Rs 2,200 crore to buy 51 per cent of the business. And the business would now have to earn a high return.

That may not be difficult. The cement market is growing at 8 per cent and no greenfield capacities are viable at current costs. D.D. Rathi, Executive director of Birla's flagship cement company Grasim, feels that there will come a time in the near future when the demand will far exceed supply. When that happens, the price realisations for cement (at $40-45 a tonne, they are currently far lower than international benchmarks of $60-80) will go up. That will immediately have a huge impact on Grasim's margins. (With gross margins of 28.2 per cent, Grasim is already reckoned to be among the most profitable cement companies in the world.) Rathi says they will add small chunks of capacity to grow market share. But focus will clearly be on consolidation.

As the aluminium, copper and cement businesses take shape, there is one common strand running through Kumar Birla's new growth strategy: at a time when Indian businessmen are furiously expanding overseas and buying up foreign assets, Birla has chosen to sink almost all his major investments in India. This may seem ironical, especially since, frustrated by the regulatory environment, Kumar's father, Aditya Vikram Birla, was among the first Indian industrialists to establish global outposts, way back in 1973.

It may appear as if the wheel has come full circle. But Kumar Birla would perhaps feel that in a rapidly globalising environment, his journey has only just begun.