The organisation man

17 July, 2005 | Business Today

ShareBusiness Today

17 July 2005

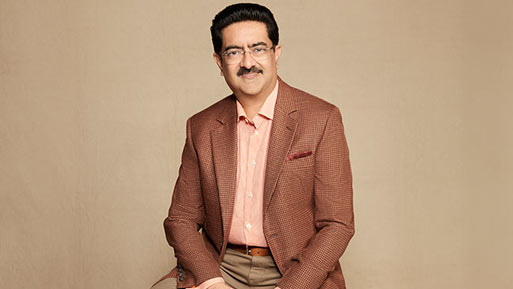

At 38, Kumar Mangalam Birla has already done more than what most others get to do in a lifetime. He's transformed a hidebound conglomerate into a modern commodities giant that's globally competitive. How did he do it? By not acting his age.

At 38, Kumar Mangalam Birla has already done more than what most others get to do in a lifetime. He's transformed a hidebound conglomerate into a modern commodities giant that's globally competitive. How did he do it? By not acting his age.

>Had Kumar Mangalam Birla been a director or a writer, he would have made a movie like the Wachowski brothers' Matrix or penned a breakthrough book like C. K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel's Competing for the future. That's a hypothesis. The 38-year-old Birla, he informs you, has no plans of making a movie or writing a book; the hypothetical trivia is instead a convenient window into the mind of a man who, as a 28-year-old, rose to the challenge of turning a sprawling and hidebound family business into a modern conglomerate. It points to a man who, despite being only 38 today, thinks and acts like one vastly more mature (he was only 31 when Sebi appointed him to chair a path-breaking committee on corporate governance — a pointer to the fact that he's thought of in the same league as Ratan Tata, Deepak Parekh and N.R. Narayana Murthy, all of them considered eminence grises of India Inc.). It also points to a man who likes to push the boundaries of his sprawling business empire not by issuing edicts, but by getting his people to buy into his vision. The question, though, is, how does the Chairman of the Aditya Birla Group see himself? As a custodian of the hoary Birla legacy or as a catalyst of change? "My calling is to build an organisation that can c;reate value; anything else is a subset of that," declares Birla. "There is an element of legacy here, but I don't see myself as a catalyst of change as such, only change as a subset of organisation building."

Don't mistake the modesty for diffidence. It's simply that in the young Birla's scheme of things, the organisation comes first. Over the last 10 years, the strategy of putting the organisation above everything else has worked wonderfully well. When he succeeded his father, who died in 1995 at the age of 52, the group had revenues of Rs 8,000 crore and a market cap of Rs 8,000 crore. Today, it racks up Rs 33,000 crore in revenues and boasts of a market cap of nearly Rs 30,000 crore. In that time, he has also pulled off a string of acquisitions at home and abroad, professionalised a group that long placed loyalty over competence, and more importantly geared it to compete in a global marketplace.

As a result, the Aditya Birla Group today operates on a global scale, with manufacturing operations in nine countries and product sales in over 100. It's a world leader in viscose staple fibre, the world's ninth largest producer of cement, the fifth largest producer of carbon black, Asia's largest integrated aluminium producer, and also its fastest growing copper company. Not incidentally, his is also the most successful of all the Birla groups that were spawned after patriarch Ghanshyam Das (G.D.) apportioned assets among his sons and grandsons. Says Kumar Mangalam's grandfather, Basant Kumar Birla: "My style of management was no different from my father's (G.D.) and Aditya's was about 20-25 per cent different from mine, but Kumar Mangalam's is completely different."

That's actually saying a lot. In traditional Marwari business families, scions aren't expected to have a mind of their own. Typically, they are expected to continue family traditions and customs, and play the benefactor babu. In Kumar Mangalam's case that's all the more surprising, given that he — being the only son — was personally groomed by his father. In fact, Aditya Vikram started involving his son in the family business when he was not yet 20. Even as a college student, the young Birla would hang around his father's office just watching him at work and picking up lessons in the art of management. And when Kumar Mangalam returned from London with an MBA, he was sent to Hindalco's Renukoot plant in Uttar Pradesh to cut his teeth.

That's actually saying a lot. In traditional Marwari business families, scions aren't expected to have a mind of their own. Typically, they are expected to continue family traditions and customs, and play the benefactor babu. In Kumar Mangalam's case that's all the more surprising, given that he — being the only son — was personally groomed by his father. In fact, Aditya Vikram started involving his son in the family business when he was not yet 20. Even as a college student, the young Birla would hang around his father's office just watching him at work and picking up lessons in the art of management. And when Kumar Mangalam returned from London with an MBA, he was sent to Hindalco's Renukoot plant in Uttar Pradesh to cut his teeth.

Somewhere along the way, it seems, Kumar Mangalam developed a distinctive mind of his own. If his father Aditya Vikram ran the group with the zeal of an entrepreneur, Kumar Mangalam does so with the passion of a coach: building a great team, setting the goals and then inspiring it to achieve those goals. It's not too hard to see why. In the days of his father, managing the external environment (swinging licences, getting permits and clearances from the government) was the main challenge. There was little domestic competition, and foreign players hadn't yet been let in. The world that Kumar Mangalam operates in is vastly more complex. Tariff barriers are coming down with every passing year, benchmarks of quality and cost are global, and scale and competence have become crucial to survival. Kumar Mangalam's answer to the unprecedented challenges has been simple: "He has assembled an impressive bunch of professionals and he listens to them, while he himself scans the environment to anticipate changes," notes R. Gopalakrishnan, Executive Director, Tata Sons.

In retrospect, turning a patriarchal group into meritocracy may seem easy. But the fact is, that's possibly the biggest challenge Kumar Mangalam Birla has had to face so far. According to his grandfather, Kumar Mangalam Birla once had to let go of 350 people above the age of 60 in one day — most of these people were old loyalists who had worked for Aditya Birla for years. So retiring them couldn't have been easy for Kumar Mangalam too, but he did it because, well, he had to — the needs of the organisation demanded that he do so. "People in the group were about twice my age when I took over as Chairman. I had great respect for them personally, but I also felt the need for change," he says.

Change things Kumar Mangalam did. To start with, he decided to put in place non-existent HR systems, and roped in Santrupt Misra from Hindustan Lever. Others like Bharat Singh, Debu Bhattacharya, Sanjiv Aga, and Sumant Sinha, son of former Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha, soon followed. Sinha, an lIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta grad, had worked as Vice President with Citicorp and as a director with ING Barings for the Asian region, when Kumar Mangalam approached him. Sinha, reports go, held out for a year, but capitulated when he bumped into Birla in Goa (both were on a family vacation) in 2002. Says Sinha: "I realised that I was walking into an entrenched system and couldn't do so with my eyes closed. But the only reason I ended up joining was Kumar Mangalam Birla."

In hiring Sinha as President (Finance), Kumar Birla was also sending out a signal to other CFOs in the group. That the focus was shifting from cost alone to value creation. "My task here is to enhance the value of capital — that's the diktat from Mr. Birla," points out Sinha. Working with the Boston Consulting Group, the Aditya Birla Group developed a Cash Value Added metric to ensure that equity holders got their due. That gradually evolved into an Economic Value Added metric three years ago. "These may just sound like measure metrics, but the mindset change (they bring) in the organisation is huge," says Sinha. "Each business has identified a benchmark equity return for itself." The group CFOs meet once a month to chalk out strategies for treasury, forex and risk management, besides addressing other common issues.

The group has evolved an ingenious management system that allows for individual businesses to function to their optimum under their respective managements, while leveraging the expertise of those in the Aditya Birla Management Corporation Ltd (ABMCL) — a group which is actually physically assembled at the group headquarters in central Mumbai. "You could call this the central nervous system of the group and two kinds of people are here — those with groupwide responsibilities, and all business leaders, that is, CEOs of individual businesses," explains Santrupt Misra, Director, Aditya Birla Group.

The group has evolved an ingenious management system that allows for individual businesses to function to their optimum under their respective managements, while leveraging the expertise of those in the Aditya Birla Management Corporation Ltd (ABMCL) — a group which is actually physically assembled at the group headquarters in central Mumbai. "You could call this the central nervous system of the group and two kinds of people are here — those with groupwide responsibilities, and all business leaders, that is, CEOs of individual businesses," explains Santrupt Misra, Director, Aditya Birla Group.

About 20 business leaders and those with groupwide responsibilities housed at the headquarters report directly to the Chairman, whose doors are always open to his direct reportees. Not even his secretary is allowed to get between him and them. He gives them complete freedom to run their businesses, but also holds them accountable for their performance. "Delegation for me is a given," he says. "If the person feels he can't take responsibility then I am the wrong person to work for." Adds Misra: "Mr. Birla starts from a position of trust and continues to do so unless proven otherwise, but it is in no way abdication. He has his own antennae and picks rare moments to assess people. If you pass muster at those points, then you have his trust forever."

Sanjeev Aga should be able to vouch for that. When Kumar Mangalam decided to merge his three way telecom joint venture (AT&;T and Tata were the partners, which led the media to brand it Batata, but now it's called Idea) with BPL Communications in 2001, he had publicly announced that Aga, who was heading the telecom venture, would be the CEO of the new entity. The same evening that statement was retracted by the company and an embarrassed Aga subsequenly resigned from the telecom company (the merger too never went through eventually). It's a minor miracle that he didn't quit the group — thanks, of course, to Kumar Mangalam, who assured him that there were enough challenges within the group to occupy him. "You put your cards on the table and allow people to take a call. That's what works for me," says he. Last month, Aga took over as the Managing Director of Indian Rayon.

At the core of Kumar Mangalam's management style are the twin virtues of patience and persuasion. He employs that not only with his own people, but also with associates outside. A classic example of that is the group's acquisition of L&;T's cement division. Negotiations for the deal stretched over two years — long enough for a less-dogged CEO to walk away from it. But Kumar Mangalam kept at it relentlessly.

Let's hear it from the man who had the most intimate knowledge of it, L&;T's never-say-die Chairman and Managing Director, A.M. Naik. "His style, very simply put, is to win over the person across the table with a lot of patience. He just won't give up. He is very charming and friendly even in the thick of negotiations. He gets exactly what he wants by actually winning you over."

Determination, no doubt, comes from focus. In Kumar Mangalam's case, though, that's not something new found. Ever since the young Birla started giving media interviews, which was 11 years ago, he has been consistent in the vision he has been articulating for the group. The themes have always been sticking to the knitting of core commodity businesses and gaining dominance in each of the businesses. "I am very clear that this is a conglomerate model," he says. "There are several examples of this all over the world; GE is one," says the man who strongly believes in work-life balance. (Just as an aside, when Kumar Mangalam was negotiating the L&;T cement deal, he made it a point to make time to attend, on each of the nine days that it lasted, a Ramayana performance produced by his wife Neerja and starring two of his children.) Observers like Gopalakrishnan of Tata Sons say that his focus on commodities is part of a well thought out strategy. "It's clear that India and China are in a phase of demand for infrastructure that the US was in about 60 years ago. He's obviously realised that," says Gopalakrishnan.

What explains Kumar Mangalam's forays into so-called new economy businesses such as IT, ITES, and telecom (he's also in insurance and apparel)? "We are making the move from mature businesses to businesses for tomorrow," he says, yet admits that even over the next 10 years the group will remain commodities heavy. Says one investment banker, who has tracked the group's strategies: "Birla seems to want to avoid industries that are subject to any form of regulation. He exited Mangalore Refineries &Petrochemicals (the group sold its 37 per cent stake in 2002) and now he seems to want to exit Idea Cellular."

Kumar Mangalam does not deny that he's uncomfortable with regulated industries. "That's a fair observation. In a rapidly globalising economy, where you have tariffs coming down, there are already too many variables. In that context, regulation becomes one more variable that you'd rather not deal with," he says. Does he really plan to exit Idea and, therefore, the telecom space? "No, I haven't quite decided. I may not eventually exit Idea; we are in the process of deciding," he answers tactfully. (There are rumours that he may be eyeing BPL Communications, which is looking for a strategic partner.)

While the Aditya Birla Group has excelled in the commodities business and is possibly the lowest-cost producer in the world of most of the commodities it makes, it is in the customer-facing businesses that its real challenge now lies. How prepared is the group for this new challenge? "There is a clear morphing of commodity businesses into customer-facing businesses. What seemed like a commodity business is already getting brand-driven, so there is no sharp delineation anymore," says Kumar Mangalam. "The way to insulate commodities from business cycles is to go downstream and closer to the consumer — like going from cement to ready-mix concrete, from aluminium to foil for housewives," he explains.

As for the new economy businesses, he is particularly bullish about BPO, while "IT hasn't taken off the way we thought, but that could change". And as for Madura Garments (group company Indian Rayon acquired it in 2000), the idea, he says, is to turn it into a completely retail-focussed company, given that there's an explosion of malls and, hence, organised retail.

But then, like he says elsewhere, these will remain a small sub-set of his larger commodities empire. And here is where Kumar Mangalam must feel that his biggest challenge lies. It's a challenge that involves, on the one hand, making the commodity businesses of aluminium to viscose staple fibre to fertiliser (with apologies to Sam Walton) every day more competitive and, on the other, making sure that their value on the stock market goes up. After all, the group's market cap today is much less than its overall revenues. It's no ordinary challenge. But, then, Kumar Mangalam has proved he is no ordinary young man.

Milestone achievements

Cement

1998 Indian Rayon's cement business transferred to GrasimGrasim acquires Shree Digvijay Cements for Rs 65 croreGrasim acquires Dharani Cements for Rs 466 crore

2004 Grasim acquires controlling stake from L&;T in UltraTech Cement; deal-size Rs 2,200 crore

Aluminium

2000 Hindalco acquires Indal for Rs 1,018 crore, merges it with itself in 2004

2005 Hindalco signs MoUs for integrated greenfield projects in Orissa and Jharkhand

Copper

2003 Hindalco acquires Mount Gordon Copper Mines in Australia for A$21 million

Hindalco acquires Nifty Copper Mines in Australia for A$80 million

Hindalco merges Indo Gulf's copper business with itself

New ventures

2000 Indian Rayon acquires Madura Garments for Rs 230 crore

2001 Indian Rayon acquires PSI Data Systems from Groupe Bull of France for Rs 100 croreIndian Rayon enters JV with Birla Sunlife Insurance

2003 Indian Rayon acquires BPO outfit Transworks for Rs 69 crore